Be the Best Belayer Ever

Whether you’re introducing climbing into your repertoire of adventurous hobbies or you’re already a veteran of this glamorous sport - if you’re hooked like the rest of us, you’re likely striving to achieve your personal best. How we evolve into the Best Climber we can be is dependent on many, seemingly ungovernable factors such as strength, athletic ability and technique. Conversely, how we evolve as Belayers is totally within our control.

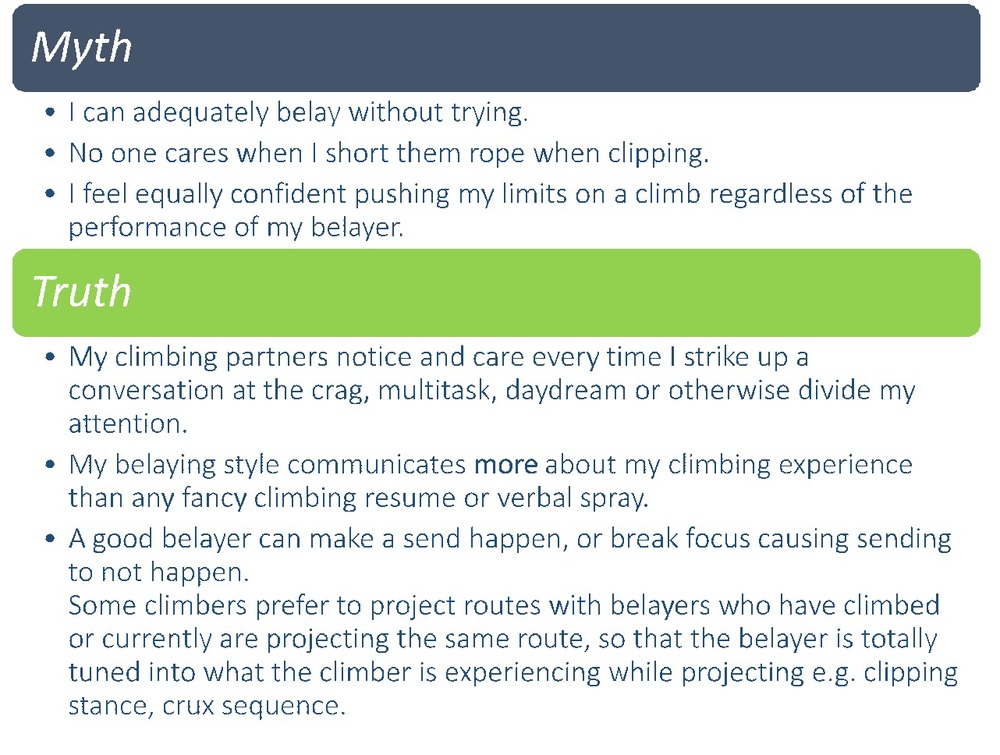

While our climbing performance can fluctuate wildly from one day to the next, every time we belay we should be performing consistently and at our best. Consider the alternative: the consequence of performing subpar as a belayer can cause safety hazards, undue stress, loss of friends or friendships, loss of climbing days.

Essentially, no one wants to be belayed by a bad belayer. Thus, half of striving to achieve our personal best within the sport of Climbing should also be evolving into the Best Belayer we can be.

For the past weeks, I’ve climbed with strangers and friends alike, and used their experience as resource for this blog post. When interviewed, an overwhelming amount of seasoned climbers described their Perfect Belayer as Present, Attentive, and Communicative – all key points we’re discussing today.

To build the best belayer, we must first lay the foundation of Technique and Knowledge.

The Will to Learn

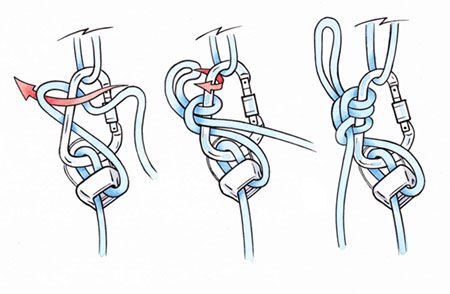

During a climbing trip to Rifle, while belaying I noticed I would (annoyingly) occasionally short the climber rope. Once, it happened to a friend who scolded me and asked to be lowered off his project. I apologized and said it was happening more often with the new GriGri 2. He asked if I had watched the instructional video on how to belay with the new design. I drove into town that afternoon, found internet and streamed the video. With new insight, I returned to the crag and convinced my buddy that I had overnight become the best belayer I could be. Everyone lived happily ever after. The End.

As much as possible, both our climbing ability and our belaying ability should evolve simultaneously and with an equal amount of Importance and Intention.

The learning process is collaborative and includes having knowledge about:

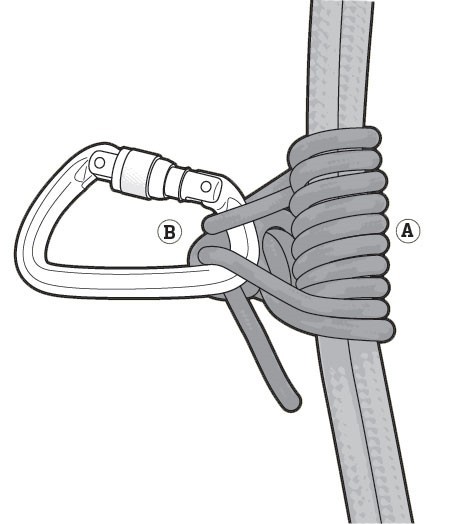

- How to appropriately use your equipment;

- Setting up or stacking the rope appropriately; and

- Setting up your stance appropriately.

Of course, one’s ability to learn anything is completely dependent on how much they apply themselves to the learning process.

Today, the average consumer researches 89% of their purchases, myself included. Most of the items I am researching are not equally researched by their manufacturing entities, proven by the large percentage of returns Amazon.com may receive from my house each month.

Uniquely, the climbing equipment manufacturing industry researches 100% of their manufactured climbing hardware, including belay devices. Further, said test results are published online, for free, usually alongside similarly useful manuals and instructional videos.

While not overwhelmingly dramatic and exciting for some (myself excluded), said resources are incredibly helpful in strengthening one’s belay technique. Free knowledge!

Own Your Role: The Expert Support Crew

"You miss 100% of the shots you don't take." Wayne Gretzky

How did Wayne Gretzky achieve multiple career records of most regular season goals (894), assists (1,963), points (2,857), and hat tricks (50)?

How would Mario Andretti have taken home 12 Formula One championship trophies without a stellar support crew?

How do Chris Sharma, Joey Kinder or Lonnie Kauk repeatedly establish and send hard routes?

The commonality between Gretzky, Andretti, Sharma, Kinder and Kauk is behind all their exceptional successes, these athletes have solid Support Teams made up of people striving to use all their resources and capabilities to execute their supportive role flawlessly, expertly.

Consider Belaying as similar to being a Support Team to a climbing partner. As a Support Team, the belayer must be alert, physically available, and have intention for the moment. When not any or all of these things, the Climber is the one that pays the price. Similar to any athlete, no Climber performs better when their focus is compromised. A short catch, a shorted clips, blatant daydreaming or inappropriate crag chat all can translate up the rope to the climber that the belayer has clocked out.

Last night I projected a route at a local crag with a new climbing partner. While I was working the crux, he asked me what else I wanted to climb next, you know, after I was finished with the climb he just projected. He went onto suggest a few routes, not noticing that I wasn’t interested in discussing a future beyond my current project. Consequently, his belay sucked, e.g. the rope was too tight, and a few times when I requested slack or tension and received neither, I looked down and saw him staring off into the distance, seemingly daydreaming. Later we chatted about where his head was at. He admitted to be totally checked out, bummed that he didn’t send, and was about 5% concentrating on belaying. We laughed it off over a beer.

Some climbers want to be koo’d, talked to, coaxed on, roasted, yelled at, coached. Some want silence. Some want beta and others do not. Some want the rope tight when projecting, and others want a slack system to give them room to maneuver. Some want both at different times. A good belayer recognizes all of this and does their best to accommodate the preferences of the climber, not themselves.

Communication

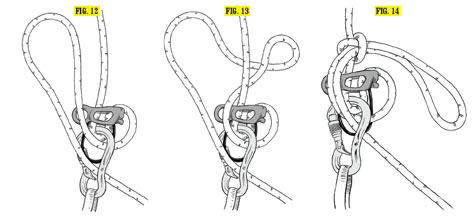

One of our local crags is the Owens River Gorge, a climbing area known for single pitch sport routes. Most of the climbs have been established or retrofitted with a mussy hook anchor system, which avoids the need for a climber to rethread or rappel off the anchor. Rarely do you hear “Off belay” spoken at the ORG, so it surprised me when a death at the crag occurred when a climber/belayer duo misunderstood each other. The climber told the belayer “off belay” which was heard by neighboring parties, and the belayer followed instruction, however the climber leaned back as if to lower. Unfortunately, the climber didn’t survive the fall.

In the AAC’s 2013 Accidents in North American Mountaineering publication, it was reported that 22% of climbing accidents related to Lowering Incident are caused by Miscommunication. Factors that can interfere with climber/belayer communication are:

- Crag noise e.g. people, pets, traffic, running water;

- Wind and/or weather;

- Differences in language or climbing commands;

- Terrain factors.

All of above can happen relatively spontaneously and simultaneously. Accidents are more likely to happen when one or more of these factors exist AND there exists no clearly defined plan of action. Thus, regardless if I am the climber or if I am belaying, I much prefer to discuss with my climbing partner our plan of action when we’re face to face rather than a pitch away from each other. It takes a fraction of time to come up with a plan when both parties are face to face and is hugely more efficient than becoming the loud party stuck on a pitch trying to communicate “off belay” or “on belay” around a corner and 60 meters apart.

In 2013, the AAC’s Accidents "Know Your Ropes: Lowering" article by Mike Poborsky speaks to proper communication techniques and suggests ways to eschew lowering accidents. I highly recommend picking up a copy of this enlightening publication.

Consider it further Inspiration to be the Best Belayer You Can Be.

Next up, find the perfect climbing partner!

|